I reviewed a book once, starting by commending the excellent printing quality, binding, and finishing of the book. I was proud that the book was made in my own country, at the book making town of Ibadan.

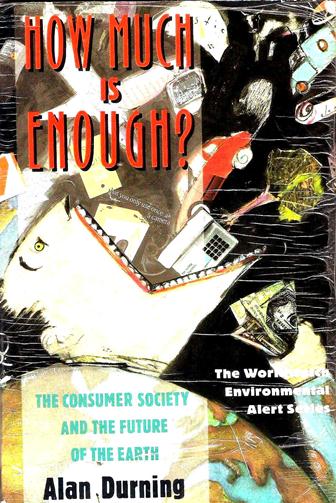

Once again, let me start this review by discussing the cover illustration which, after reading the book’s content, you will agree with me that it effectively summarises the whole work.

The cover depicts a monstrous head of a white man (supposedly American) with a mouth wider than the largest crocodile imaginable. The large human head has a body made of the entire earth. Its crocodile mouth is spread wide open, receiving and gulping down all sorts of manufactured goods – cars, telephone, airplanes, TV sets, artificial trees, etc., made from rapidly dwindling earth’s resources.

The right hand of this leviathan clutches wads of US Dollars (no doubt in high denominations) which gives him access to all products and a lifestyle of profligate consumerism.

The book has three broad divisions – (I) Assessing Consumerism. (II) Searching for Sufficiency, and (III) Taming Consumerism. Within these three broad divisions are further subdivisions.

Under Assessing Consumption, the author discusses (1) The Conundrum of Consumerism, (2) The Consumer Society, (3) The Dubious Rewards of Consumption, and (4) The Environmental Cost of Consumption.

In Search for Sufficiency, the author treats (5) Food and Drinks, (6) Clean Motion, and (7) The Stuff of Life.

Finally, in Taming Consumerism, which addresses the issues raised, Alan deliberates on (8) The Myth of Consume or Decline, (9) The Cultivation of Needs, and (10) A Culture of Permanence.

The major research question upon which this ecological treatise hangs is cast on page 24: Is there a level of living above poverty and subsistence, but below the consumer lifestyle – a level of sufficiency?

This question recognises that poverty and subsistence on one hand, and unbridled consumer lifestyle on the other hand, are two extremes – ill winds that blow nobody good.

Other follow-up questions are: if the environment suffers when people have either too little or too much, how much is enough? What level of consumption can the earth support? When does having more cease to add appreciably to human satisfaction? Is it possible for the entire world’s people to live comfortably without bringing on the decline of the planet’s natural health?

More question: Could the entire world’s people have central heating, refrigerators, clothes dryers, automobiles, air conditioning, heated swimming pools, airplanes, second homes, etc.?

The fact is, argues the author, the global environment cannot support 1.1 billion of us living like American consumers, much less 5.5 billion (over 7 billion presently) or a future population of at least 8 billion.

Based on a UN data for 1987-88 on “Role of Unsustainable Consumption Pattern and Population in Global Environmental Stress,” industrial countries whose people make up only one fourth of the global population, consume 40-86 percent of the earth’s natural resources.

This reckless consumer lifestyle was born in USA and exported to other parts of the world. On page 21, the author quotes the ecologically notorious statement made by the American, Victor Lebow after 2nd World War: ‘Our enormously productive economy … demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption … We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing rate.’

Now, pricked in conscience by his environmental sins which resulted in pollution, global warming, loss of genetic diversity, deforestation, unprecedented waste generation, etc., an American geologist, Sidney Quarrier, in chapter one of this book, takes stock of all the damage his consumer lifestyle is inflicting on the local, regional, and global environment.

Environmental damage is a subject most people, organizations, and governments, shy away from discussing because almost everyone – especially the affluent – are culprits. At best, they prefer to pay only lip service to the problem and continue to live their unfriendly environmental lifestyle – burning tons of fossil fuel, releasing tons of carbon dioxide into the environment, inefficient energy use, refusal to reduce use of air conditioner, etc.

The way out is for the consumer society to drastically curtail its use of resources and this can be done by shifting to high-quality , low-input durable goods, and also by seeking fulfillment from other sources like leisure, human relationship, and other non-material avenues.

Survey by Lewis Lapham on page 38 confirms that human desires are expandable, and so consumption is incapable of providing fulfillment. “Nobody ever has enough.”

The happiness people derive from consumption, argues the author, is illusory, because it is based on whether they consume more than their neighbours (I better pass my neighbour) and more than they did in the past. Buying and consuming things becomes a proof of self esteem that says, “I am worth it,” – a means of meeting up with the Joneses.

The definition of a “decent standard of living in a consumer society endlessly shift upward because “needs are socially defined, and escalate with the rate of economic progress.” Besides, sudden wealth can make people miserable as it often does many a million dollar lottery winners.

Alan cites another survey conducted by Jeremy Seabrook concerning people’s experience in rising prosperity. “People aren’t satisfied,” one respondent told Seabrook, “only they don’t seem to know why they are not. The only chance of satisfaction we can imagine is getting more of what we’ve got now. But it’s what we’ve got now that makes everybody dissatisfied. So what will more of it do, make us more satisfied, or more dissatisfied?”

Accelerated pace of life is another dubious reward of consumption. As nations get richer, they hurry up. The more people value time – and therefore take pain to save it – the less able they are to relax and enjoy it.

High consumption also means huge environmental impacts. Fossil fuel burnt in industrial countries release carbon dioxide of which the consumer class is responsible for estimated two thirds of all emissions from this source and up to three fourths of the sulfur and nitrogen oxides that cause acid rain. The more than 450 million vehicles in USA (as at 1992), says the author, accounts for 13 percent of global carbon emission from fossil fuels

Infected by the consumption virus, third world and developing nations, in an effort to attract foreign companies’ investments that will bring the American pattern of consumption to their countries, throw cautions and regulations to the winds.

“From global warming to species extinction, we (Americans) consumers bear the burden of responsibility for the ills of the earth,” Alan admits.

On food and drinks, while a larger fraction of the world’s population suffer hunger, one fourth of the world’s cropland goes into growing grains for animals that produce the meat of the consumer class. Well, heart diseases, stroke, cancer of the breast and colon – diseases of the affluent – are the prizes the consumer class pay for their meat-rich diet.

Besides, the processing, packaging, distribution and storage of the food and beverages of the consumer class tell on the earth, both in terms of the materials they take – metals, glass, paper and plastic – and the waste they generate after consumption. Tomatoes, green peppers and some fruits that last only about a week are sold in plastic bags that last more than 100 years as refuse. In one of his stunning statistics, Alan records that the world tosses away at least, 200 billon bottles, cans plastic cartons and paper and plastic cups each year.

Lots of the foods of the effluents, even the flowers that decorate the tables of the rich, travel long distances to reach them, which further hurts the environment.

How can these problems be solved? Already, millions of people in the consumer class who have cars and conscience leave their cars behind, walking, bicycling, or riding public transport to and fro work and other destinations. Aspiring for cities in which cars are used less because they are needed less, where people work and shop close to home, take excursion by public transit and travel longer distances mostly by train will ensure clean motion or clean energy thereby contributing to safety of the global environment.

Also ingrained in consumerism are the throwaway culture and what the author calls planned obsolescence. This is a deliberate manufacturing policy that makes machines and other gadgets impossible to repair when they spoil. Sometimes, the cost of repair, when weighed with the cost of new one, makes little or no economic sense. Some formerly recyclable stuff like papers and plastics can no longer be recycled due to some in-built components. The result is mountain of wastes in cities and diminishing sources of raw materials.

The rich are also obsessed with gold, diamonds, and other so called precious gems and metals which have no tangible or intrinsic values. As a result of their voracious appetites for these gems, miners tear the bowel of the earth into pieces, disturbing ecosystems and vandalising the environment.

The world, therefore, must return to the culture of repairing things, reusing and recycling materials. Caring for the earth, writes Alan, means caring for the things we take from it.

There is a lie canvassed (supposedly by greedy consumption addicts) that without consumption of this magnitude workers will lose their jobs and there will be no more markets for the raw materials of the over 42 poorest countries. Against this argument, the author says: business will not do well on a dying planet either.” If we attempt to preserve the consumer economy indefinitely, ecological forces will dismantle it savagely.

The author accuses commodity advertisement, with their high sales pitches, of complicity in cultivating the consumer society’s needs. Moreover, newspaper advertisement needs papers and that means cutting down trees and destroying forests which are the livewires of planet earth and its organisms.

Realising the environmental unfriendliness of their business practices, business organsisations now engage in what the author calls “green gimmicks” aimed at misleading the public and consumers into believing that they care for the environment and that their operations are environmental friendly when in reality they are not.

The grand solution to the consumer culture problem therefore is to evolve a culture of permanence – a way of life that can endure through countless generations. This will require us, as has been mentioned before, to cultivate the deeper, non-material sources of fulfillment – family, social relationships, meaningful work, and leisure. The ecological golden rule is: each generation should meet its needs without jeopardising the prospect for future generations to meet their own needs. This is what is called sustainable development, or in this case, sustainable consumption.

Very few authors have addressed ecological problems as did Alan Durning in this book. He has the required knowledge, data, statistics, and the precise creative language which makes How Much Is Enough? irresistible to readers.

Subtitle: The Consumer Society and the Future of the Earth

Author: Alan Durning

Publisher: W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

Reviewer: OSA AMADI